Pogroms

“… it was impossible to cope with the large number of immigrants [arriving] twice a week.” Jewish Chronicle, 1891

1882 – 1914 saw the largest influx of Jews into Edinburgh and marks the community at its peak before a slow decline in numbers following World War I. This period of mass migration began as a direct result of reprisals against the Jewish population of Tsarist Russia following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881. Over 200 pogroms across the Russian Empire were recorded. This violence against Jews continued into the 1900s, causing millions to leave their homes, seeking refuge and new opportunities, mainly in North America. The numbers of immigrants rose and fell in direct correlation to events in Eastern Europe.

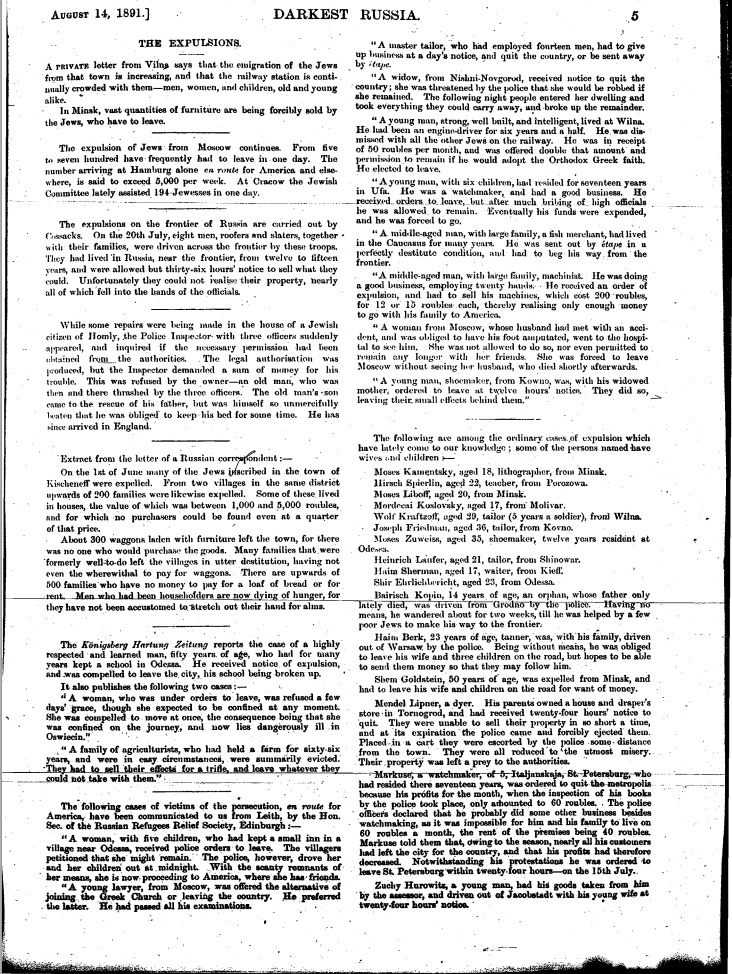

Shipping records show that the majority of Jews landing at Leith Docks passed through Edinburgh on their way to Glasgow in order to continue their journey to the USA. Others remained, either because they could afford to go no further or because Edinburgh was their destination. [View article from The Jewish Chronicle, 14/08/1891, entitled ‘Darkest Russia’.]

First World War

“We had ten in our company, all good fighters, and six won’t be seen again. So don’t say a word against the Jews.” Highlander, Black Watch

153 Jewish soldiers from Edinburgh fought during World War I, which represented a significant contribution from this small community. Twenty were killed in action, the youngest being seventeen year-old Jack Cohen. All are remembered on a memorial plaque, now in the Salisbury Road Synagogue.

The war also brought difficulties. It affected trades that traditionally employed Jewish workers, such as tailors and furriers, and brought internment or deportation for many of the city’s non-naturalised Jews. A rise in attacks against Jews and their property was also marked. This appears to have been caused by an identification of Jews with Germans, a widespread attitude in Scottish society at the time, which contained elements of antisemitism and plain anti-German feelings.

“Until Aug 15th 1914 I carried on a business at Leven, Fife. But owing to certain statements that I was a German and held pro-German views my business was wrecked by a crowd of 4,000 people and I almost lost my life owing to the hooliganism of the riot. We came to Edinburgh and I started a business for my father but owing to the persistent rumours that he was a German he had to leave again and he has been unable to get a livelihood since.” Court Statement, Simon Harris

The War did bring a degree of reconciliation however between Jewish factions in the city through the formation of the Edinburgh Jewish Representative Council, set up in 1915 to support the destitute and defend the interests of Edinburgh Jews. The sacrifice of Jewish soldiers fighting in Scottish regiments was widely recognised in the city.

The inter-war years and World War II

Following Hitler’s decree of 1933 forbidding Jews to practice their profession, Edinburgh saw an influx of professionals from Germany (and, from 1938, also Austria) which significantly benefited the cultural and academic life of the city. A number of these are featured in the interactive gallery below. Others who chose to make Edinburgh their home as a result of Nazi policies and the outbreak of the Second World War included Polish artist Aleksander Żyw and Professor Max Born who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics for his work in quantum mechanics at the University of Edinburgh.

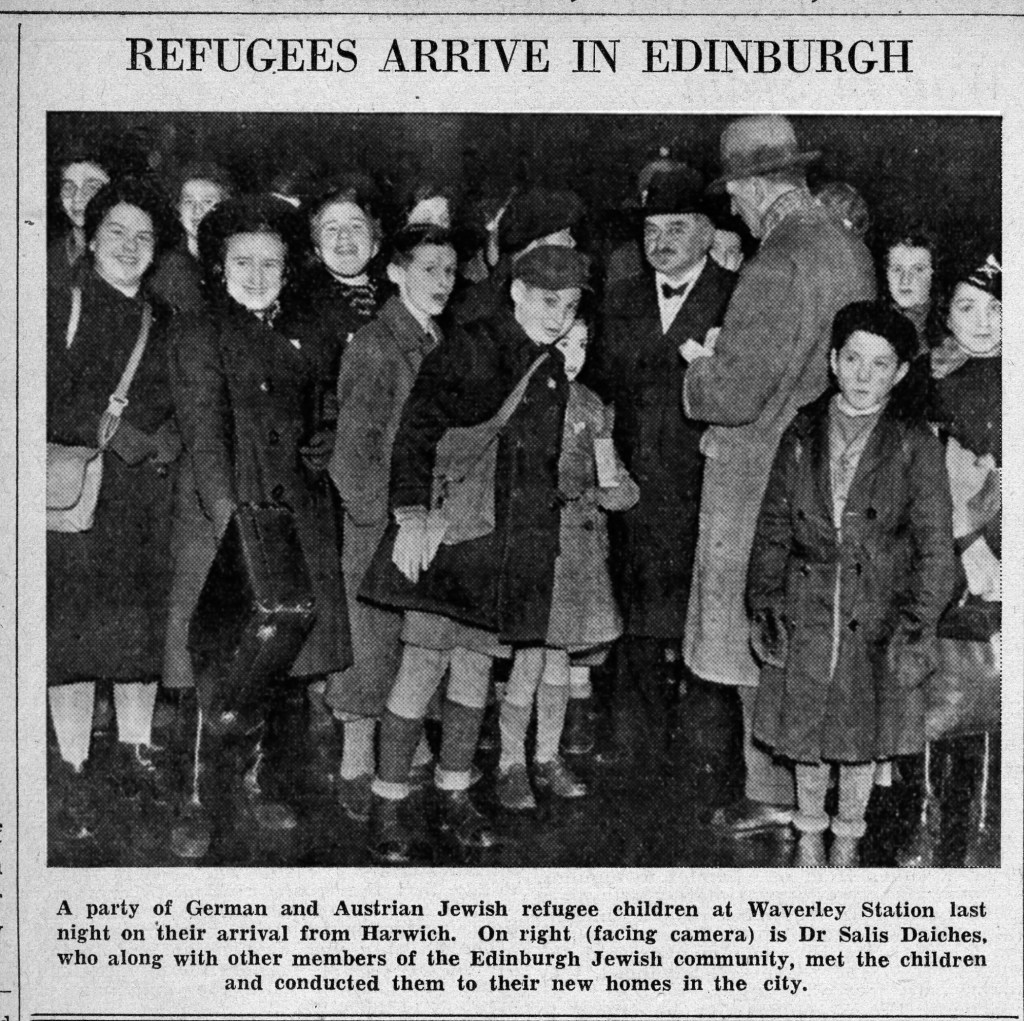

The build-up to war brought about changes in the relationship between Christians and Jews in Edinburgh. Before the unification of the Church of Scotland and the Free Church of Scotland in 1929, relationships between Jewish leaders and the leading clergy of both churches were mostly negative. This was a legacy of the sustained and intensive missionary focus of the two churches. Rabbi Salis Daiches also made frequent complaints about antisemitic accusations made by leading church officials as late as 1935. However, the worsening of persecution in Germany brought about a profound change in the stance of the Kirk, which turned towards an examination of its own attitudes, and in 1938 the first steps were taken towards the creation of inter-faith bodies in Edinburgh. On his death in 1945 Salis Daiches was commended for his pioneering efforts in bringing about a greater understanding between Jewish and Christian leaders in Scotland.

Edinburgh again saw Jewish soldiers going to war, internment of non-naturalised Jews and a further influx of refugees. The response by the majority of the Scottish population, following the arrival once again of Jews from Eastern Europe, was generous. At the same time, there was antipathy, stemming from a difficult to disentangle conflation of antisemitic and anti-German feelings.

The Kindertransport was a rescue mission begun nine months prior to the outbreak of World War II. The UK took in nearly 10,000 Jewish children from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. They were often the only members of their families to survive the Holocaust. A number of the children arriving in Edinburgh were placed at Whittingehame Farm School, where they received training in trades and agricultural work to prepare them for a future life in Palestine.

Listen to Hilda Seftor’s memories of two boys who arrived on the kindertransport and the role her family played in Whittingehame Farm School here. The relevant portion is at 25:33. There are no copyright restrictions.

You can also download the transcript of the interview here. There are no copyright restrictions.

You must be logged in to post a comment.